Lord Elgin

1776

Lord Elgin was born in 1776 into a Scottish aristocratic family, inheriting the title of Earl. After his education, he joined the military and without any combat experience reached the rank of a Lieutenant Colonel.

However his true intention was always to become a diplomat and to be involved in politics.

1790-1798

Aged 24 he was elected to the House of Lords, and in 1791 appointed Envoy Extraordinary to Austria, and for the period 1791-1793 he served as a delegate in Brussels. Consistently failing to fulfill his duties, his mission was ultimately deemed ineffective. From 1793 until 1796 he was appointed as the Deputy Minister of the British government in the Prussian court and head of the British diplomatic delegation in Berlin. Despite suffering from serious medical problems, he did not cease arranging regular parties.

1799

In search of a warmer climate due to his ailing health, he sought the position of British Ambassador in Constantinople, to which he was finally appointed in 1799. Shortly prior to his departure, he married Mary Nisbet, an heiress from a wealthy family. This proved to be a timely move, as Elgin had already accumulated considerable debts borrowing large sums of money to pull down his father’s house in Fife and building in its place a luxurious mansion, which he named Broomhall.

It was around this time that his architect, Thomas Harrison, gave him the idea of acquiring plaster replicas of ancient Greek architecture, to decorate his mansion. In his attempt to recruit the best artists, he turned to the talented painter JWM Turner but they could not reach an agreement over payment, especially as Elgin wanted exclusive rights to every drawing and painting of Turner.

Along with two secretaries, the Reverend Phillip Hunt, his wife and staff he departed for Constantinople. Once in Sicily he managed to recruit, at a better rate, the necessary workers and appointed the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri to head the mission.

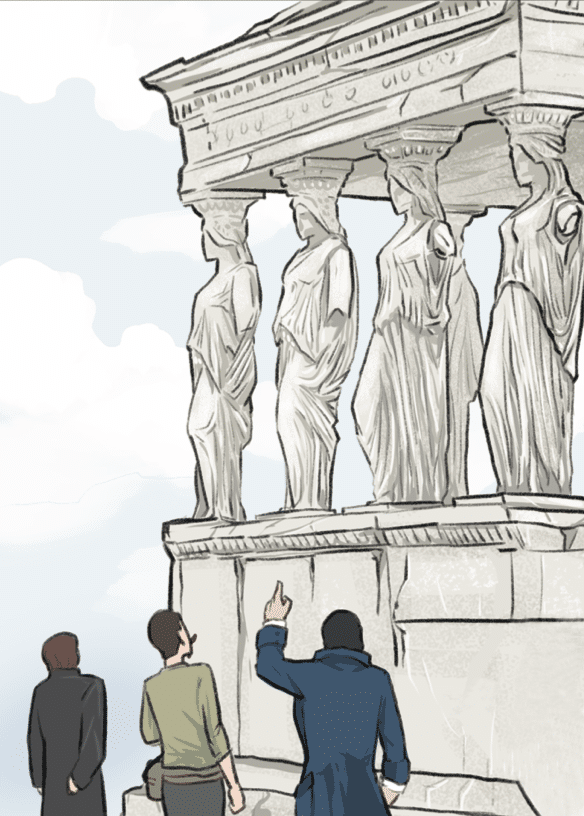

1800

Elgin sent his crew of artists to Athens, to make drawings and casts of the famous antiquities. By now the Ottomans had converted the Parthenon into a mosque, treating it with respect and care. Furthermore, the Ottomans were using the Acropolis as a military fort. For this reason, Lusieri had to bribe the officers to permit them entrance.

With the outbreak of war in Egypt between the Ottomans and the French, led by Napoleon, the artist’s only means of access to the Acropolis was with a written document of authorization from the Sultan, known as a Firman. During this time, England had joined forces with the Ottomans to defeat Napoleon in Egypt, reversing it back to an Ottoman territory. This event had a decisive and positive effect on the relationship between the Ottoman authorities and Lord Elgin as the British ambassador.

1801

Elgin wasted no time in pressuring the Turkish official in Constantinople, the Kaymakam, to issue the famous “firman”. The Kaymakam, with whom he had a good rapport, was standing in for the Grand Vizier. The content of his friendly letter is known today thanks to an Italian translation of the original, which has never been presented. According to the document, Elgin’s crew was given access to make casts, erect scaffoldings, as well as to excavate around the Parthenon’s foundation and to remove some stones with inscriptions or stones with sculptural decoration. However it was stated in very explicit terms that, under no circumstances, could the crew cause any damage to the monuments. This document is not in fact a “firman,” it was simply a letter.

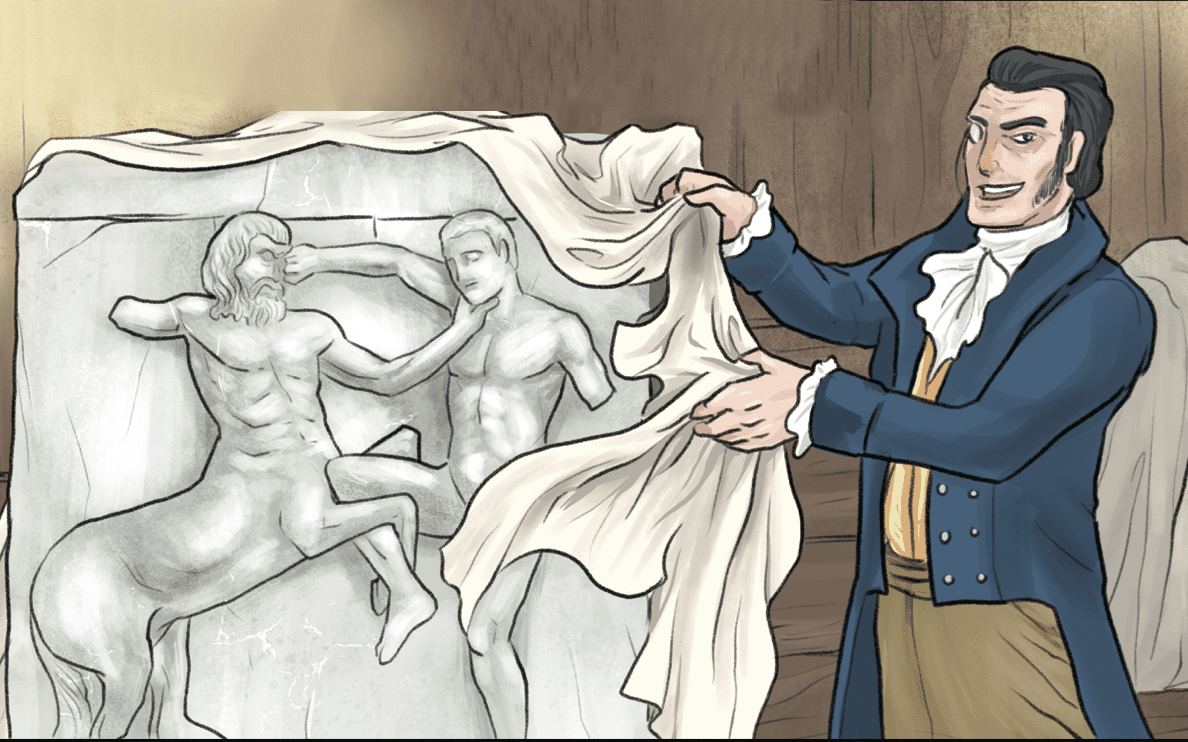

Reverend Phillip Hunt came to Athens with this letter, laden with gifts to bribe the Ottoman officials, specifically the Disdar and Voivode. By pressuring them, he managed to detach the first Metope from the temple. According to Rev. Hunt’s own words, he shivered with excitement as he watched the detachment of the beautiful sculptures, hanging in the air waiting to be lowered down with ropes. Elgin was thrilled when he learned of this unexpected success and pushed Lusieri to detach as many pieces as possible, convinced that original antiquities rather than replicas would best enhance his mansion’s beauty.

1802

Lord Elgin visited the Acropolis only after the sculptures had been removed and the Parthenon left ruined. The cornices were smashed; moreover to remove the Metopes, the triglyphs were recklessly destroyed. Due to their excessive weight, Lusieri had given orders for the backs of the friezes to be sawn off and a column to be cut in half in order to be packed and shipped to London. By accident they also cracked the centerpiece of the east frieze in two.

Edward Daniel Clark (British), was visiting Athens in 1801. He witnessed a Metope falling and smashing on the ground as Elgin’s crewmen were trying to bring it down. According to his colorfully described story, the Disdar, who was also present, shed a tear as he watched that Metope shattering. In September, Elgin’s ship The “Mentor” set sail with 17 cases of antiquities, including among others 14 pieces of the frieze and 4 frieze pieces from the temple of Athena Nike. During a violent storm, the ship sunk after it collided with rocks near Kythira’s port. It took Greek sponge-divers two years to hoist up the precious sculptures. Elgin instructed his people to claim that the cases piling up on the shore contained “stones of no value”.

1803

In 1803 Lord Elgin and his family left Constantinople to return to England to pursue his political dreams and to assemble his collection of marbles. On his journey, he passed through Athens, Kythira, Malta and Rome before being arrested in Paris as a prisoner of war. It was unknown to him that France had just declared war on Britain. Due to his ill health, he requested permission to relocate to a city called Barez, which had hot springs for his treatment. Later, he was kept captive in Lourdes and when he was released he moved with his wife to Pau, and for a short period to Orleans.

Meantime back in Athens Lusieri was busy removing more sculptures, since an Ionic and a Doric column along with the whole Caryatid porch were intended to decorate the ballroom of Elgin’s mansion. According to legend, the removal of one of the Caryatids from her sisters was so overwhelming that she could be heard crying out to her sisters from Peireus and they were replying back to her from the Erechtheion.

1804

Elgin’s successors in Constantinople disapproved of their predecessor’s actions. Also the Ottoman government gave orders forbidding Lusieri from ever entering the Acropolis. Undeterred, he continued detaching antiquities for Elgin’s collection from Olympia, Thebes, Orchomenos, Daphni, and other sites, shipping them to England via Malta.

1805

After the death of her fourth child, at age one, Lady Elgin was given special permission by the French to return to Paris. Once pregnant with their fifth child Napoleon concerned with her health, granted her permission to return to Britain to bury her lost child, accompanied by Rev. Hunt.

During this period, she began socializing with her child’s godfather Robert Ferguson, and they began an affair. In the meanwhile, Elgin was arrested for a second time and was imprisoned in Melun.

1806

Elgin was released and returned to Scotland, but by now his life had changed dramatically. He had lost his position in the House of Lords and divorced from his wife due to her affair.

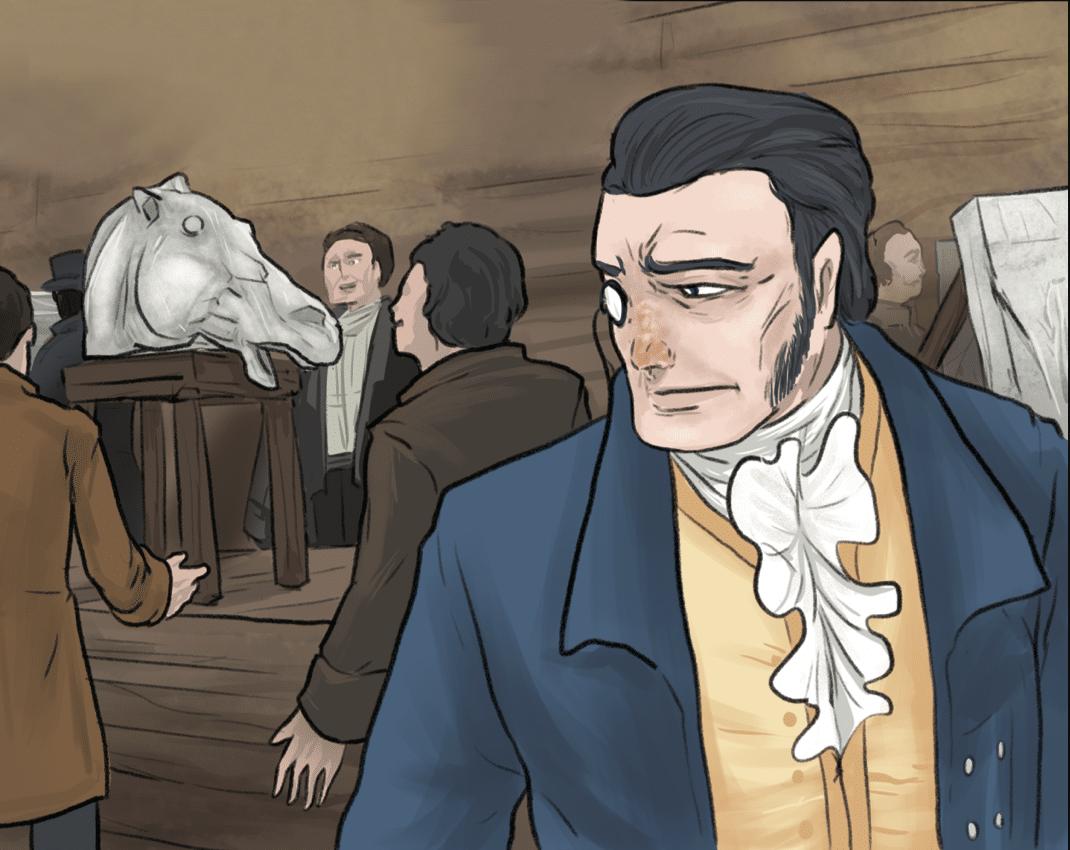

Owing to the financial burdens of maintaining such a large residence he was forced to fire all the staff of the mansion, which was by now left mostly unfurnished. Not only mired in debt as a result of the large fees, gifts and bribes he had given to the Ottomans in the previous years, his first-born son was diagnosed epileptic, and he himself had contracted syphilis causing horrendous disfiguration of his nose.

1807-1811

In 1809 Hamilton, Deputy Minister in the Foreign Office, suggested to Lord Elgin in a letter that a group of third parties could set a fair price for his collection to be sold to the British government.

Lusieri returned to Athens in 1809 to confront a difficult situation: A large number of cases containing artifacts from the Acropolis had remained piled up in Peireus throughout the war between France and Britain. He tried to charter vessels to transport the antiquities, but an order arrived from Constantinople not to remove any of the cases. Lusieri once again bribed the Kaymakam with extravagant sums of money and managed to remove the antiquities in 1810.

Again the cases were sent to England via Malta. Usually the cases had to be repaired there, as they were being shipped under very poor conditions, smashing in the ship’s hold and damaged by humidity. Their ordeal continued even when they reached British ports, where they remained unclaimed due to Elgin’s ongoing captivity in France.

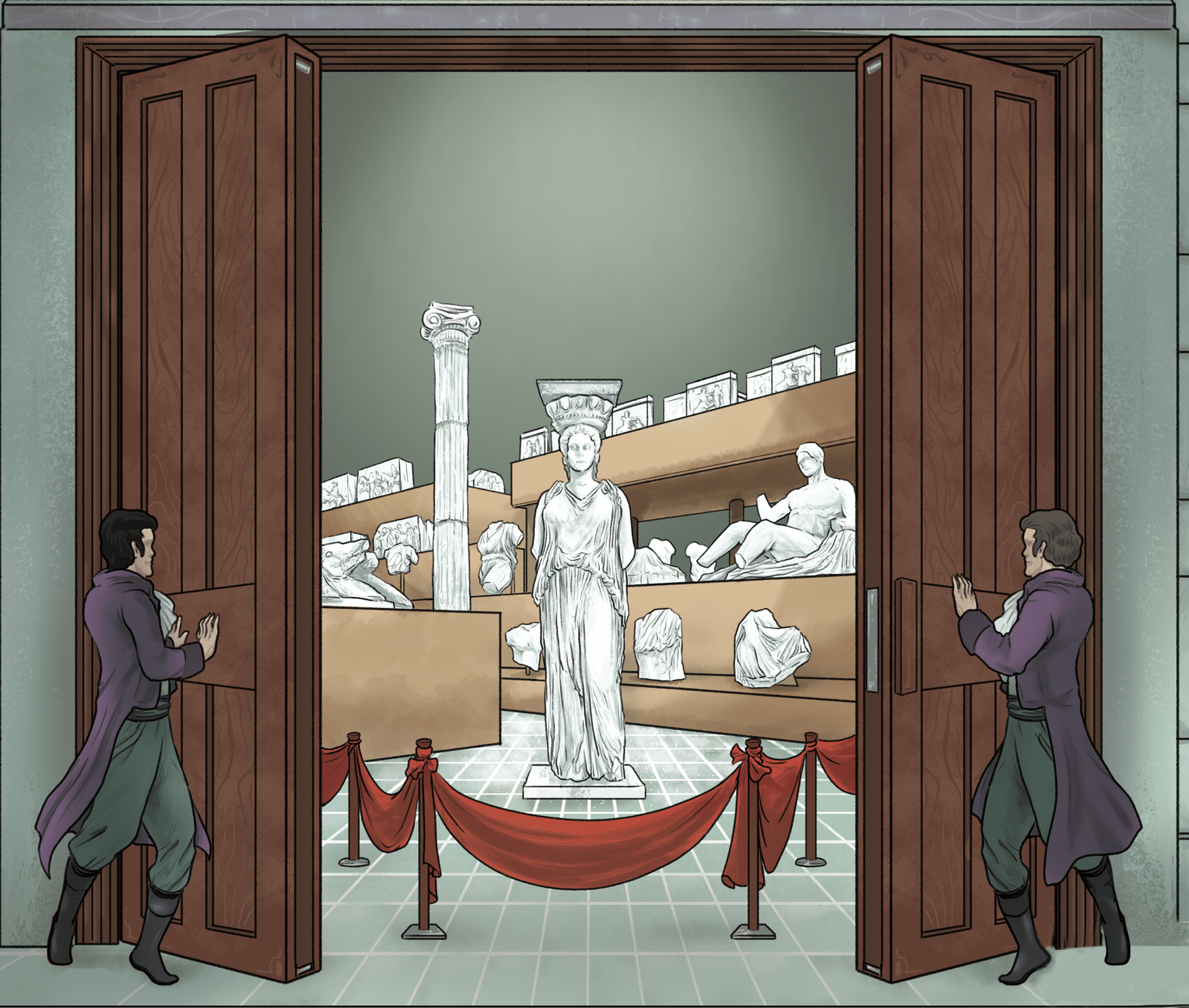

The collection was gathered in a house in London and was later left exposed in wooden cases outdoors. When Elgin returned to England he exhibited parts of his collection in the shed of another house.

In 1810 Elgin married Elisabeth Oswald, the daughter of a neighbor landowner, and together they bore eight children. Having already fathered four children from his first marriage, Elgin’s financial obligations were mounting. By now his first wife had married Robert Ferguson, and due to his high debts and lack of resources after his divorce, Elgin was forced once again to move his collection, this time into a coal shed of a mansion, as he could not even afford a warehouse in which to store them. In 1810 Elgin reached the conclusion that he should sell his collection.

1812-1816

Many people disapproved of Lord Elgin’s actions for removing the marbles. Lord Byron in particular was especially critical. The British Museum made a number of offers to Elgin to acquire his collection, and a Select Committee of the British Parliament was convened to oversee the purchase of the collection. As Elgin’s debts mounted, his collection was held as collateral. The British Select Committee, despite overwhelmingly proof to the contrary, chose conveniently to ignore that Lord Elgin had acquired his collection by taking advantage of his position as a British ambassador to Constantinople.

The British Parliament voted 80 to 30 in favor of purchasing the collection. During the deliberations, numerous criticisms were voiced over this acquisition. It was then, for the first time that the MP Hugh Hammersly proposed that the marbles should be returned to Greece as soon as conditions were favorable.

1817-1841

Elgin became an art dealer in Paris. Following Lusieri’s advice, he even sent a clock to Athens inscribed with his name as a benefactor to the people of the city. A few years later, it was burned in a fire. Some said the Athenians could no longer stand counting the hours that the marbles were away from their city. During the Greek revolution, the Turks were besieged on the Acropolis. Short of ammunition and in an effort to make bullets, they began detaching the lead joints, thus destroying the fulcrums of the columns. When the Greeks learned of this, they offered them lead in exchange for them ceasing to harm the monuments.

In 1820, Elgin returned to the House of Lords as a representative of Scotland, a position he kept until his death. Ironically, in 1821 he became a member of the Phil Hellenic Committee that supported the Greek revolution. Despite all his efforts, he ended his days owing vast sums of money. He was finally forced to flee his creditors to France where he lived penniless until his death in Paris, on November 4th 1841.